Diesel fumes

What they are, why they’re harmful and how to reduce exposure

Anyone who works with or around diesel-powered equipment or vehicles may be concerned about fumes. These are called diesel engine exhaust emissions (DEEE).

Facts about diesel fumes

- 14,728 people who died between 2000 and 2016 due to occupational exposure to DEEE, according to the World Health Organization (WHO).

- DEEE exposure limit value has been set at 0.05 mg/m3, measured as elemental carbon (EC). It came into effect in general occupational health environments in February 2023.

What are diesel engine exhaust emissions?

They are a mixture of gases, vapours, liquid aerosols and particles created by burning diesel fuels. They can contain:

- alcohols

- aldehydes

- ammonia

- aromatic compounds (benzene, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and toluene)

- carbon dioxide

- carbon monoxide

- carbon (soot particles)

- fine diesel particulate matter (ash, carbon, soot, metallic abrasion particles, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, silicates and sulphates). This can stay in the air for long periods of time, which allows the particulates to enter and penetrate deep into the lungs

- hydrocarbons

- ketones

- nitrogen

- nitrogen dioxide

- nitrogen oxide

- oxygen

- sulphur dioxide

- water vapour.

DEEE may contain more than 10 times the amount of soot particles than petrol exhaust fumes, and the mixture includes several carcinogenic substances. The International Agency for Research on Cancer, part of the WHO, has upgraded them to a group one carcinogen. They are treated as a cause of cancer in humans.

What's the issue?

Breathing in high quantities of DEEE can cause irritation in the respiratory tract within a few minutes of exposure, but prolonged exposure over many years may be more harmful.

The health effects will depend on:

- the type and quality of diesel fuel being used (for example, whether it’s low sulphur)

- the type and age of engine being used

- where and how it’s used and maintained – blue or black smoke can indicate a problem with the engine, which could mean that more toxic fumes are being produced

- the speed and workload demand on the engine

- the state of engine tuning

- the fuel pump setting

- the temperature of the engine

- the type of oil used

- whether a combination of different diesel-powered engines is contributing to overall exposure

- any emission control systems.

At the very least, short-term, high-level exposures to DEEE can irritate the:

- eyes

- throat

- nose

- respiratory tract

- lungs.

It can also cause:

- lung irritation

- allergic reactions (causing asthma)

- worsening of asthma

- dizziness, headaches and nausea.

Continuous exposure to DEEE can cause chronic respiratory ill health, with symptoms including coughing and feeling breathless. If people are exposed to DEEE regularly and over a long period, there is an increased risk of lung cancer.

- bladder cancer (and potentially other cancers such as oesophagus, larynx, pancreas and stomach)

- increased risk of heart and lung disease

- worsening of asthma and allergies.

- agriculture

- construction

- energy extraction

- fire and rescue services

- mining

- rail

- shipping

- transport and logistics

- tunnelling

- vehicle repair

- warehousing.

- airline ground workers

- bridge and tunnel workers

- bus, lorry and taxi drivers

- car, lorry and bus service and repair workers

- construction workers

- custom and border control officers

- depot and warehouse workers

- emergency service workers (police and traffic officers, firefighters and paramedics)

- farmworkers

- heavy equipment operators

- loading dock and dockside ferry workers

- maritime workers

- material handling operators

- miners

- oil and gas workers

- railway and subway workers

- refuse collection workers

- tollbooth and traffic management workers

- tunnel construction workers

- landscapers.

Lung cancer

It is agreed that the risk is linked with the particulate emissions in diesel fumes – the soot, rather than the gases or vapours. The soot is easily inhaled and drawn deep into the lungs. DEEE exposure is now often measured by the elemental carbon concentrations in the air inhaled by workers.

Even if people lead a healthy life, do not smoke or have a strong history of cancer in the family, DEEE can still cause lung cancer, depending on the number of airborne particulates the worker is exposed to.

Other health concerns from DEEE exposure

DEEE exposure can cause or is linked to other health conditions, such as:

While people are more likely to be diagnosed with a cancer caused by long-term exposure to DEEE in later life, many workers will still incur respiratory symptoms that can seriously affect quality of life at a much younger age.

Which industries are affected by DEEE?

DEEE from vehicles such as forklifts, lorries, buses, trains and tractors can cause a problem. This is particularly the case in enclosed spaces such as garages, underground car parks, vehicle test areas or workshops. People working with fixed power sources such as compressors, generators or power plants (sectors such as tunnelling, mining or construction) could also be at risk.

Exposure to DEEE can occur in any industry that involves diesel-powered equipment. These include:

Which job roles are exposed to DEEE?

People who work in areas where exhaust levels are high or can accumulate may be at risk. Job roles include:

How to manage diesel fumes

DEEE are a chemical hazard and should be managed in the same way as any other chemical – identification, assessment and control.

Identification

To identify DEEE present in the workplace, some form of monitoring is usually required. Occupational hygiene monitoring involves taking air samples over a period of time, to highlight the presence of DEEE and, if present, measuring the level.

Other ways of identifying DEEE include reviewing process-generated emissions (from diesel generators, for example) and manufacturer’s information on emissions from their equipment.

Assessment

Assessing exposure to a hazardous chemical involves looking at the type, intensity, concentration, length, frequency and occurrence of exposure to workers. This includes the amount of the chemical being produced and any indicative occupational exposure limit values, or equivalent, associated with it.

Assessment of a chemical is a subjective process. It is based on the assessor’s knowledge and experience of the chemical and the activity and environment in which it is being used. Existing controls influence how an assessor decides on the level of risk. Methods for recording this decision-making process vary. They can be numerical, using a high, medium or low scale, or a red, amber, green rating.

Legislation

National or international legislation influences the permittable level of emissions. While this is sometimes not a true reflection of the actual emissions from a vehicle or other piece of equipment, it may give some idea of expected emissions.

Check legal requirements for the country where work is taking place. Diesel quality and emission standards vary depending on the local situation, so local standards should be checked.

In European Union (EU) countries, for example, high standards are set for vehicle emissions – since 1992/93 there has been a steady reduction in allowable emissions on new vehicles including cars, trucks, trains, tractors and barges. Reductions were made in 2008/09 with the Euro 5/V standard, and in 2013/14 with the Euro 6/VI standard. In other parts of the world, standards for diesel may be lower.

Different equipment will have different standards too. A diesel generator may not be covered by some vehicle exhaust emission standards, for example, and seagoing ships may also be excluded.

Higher standards mean that the risks may be reduced, but not necessarily eliminated.

In the EU, Directive 2004/37/EC was amended in 2019. This focused on the protection of workers from the risks related to exposure to carcinogens or mutagens at work. For the first time, it included exposure limits for DEEEs.

Once DEEE are identified and the risks from them assessed, they need to be controlled. A methodology, called the hierarchy of control, can be used to prioritise controls from most to least effective.

Controls

These are the typical actions to control DEEE exposure.

- Using alternative energy sources to diesel-powered engines such as electric.

- Reducing exposure to as low as possible by purchasing low-emission engines and more fuel-efficient engines.

- Using cleaner fuels such as low-sulphur diesel fuels.

- Using exhaust gas recirculation systems to reduce emissions.

- Using tailpipe exhaust extraction systems.

- Implementing local exhaust ventilation systems and other ventilation systems.

- Using diesel exhaust gas ‘after-treatment’ systems such as catalytic converters.

- Fitting emission control devices (air cleaners) such as scrubbers, collectors and particle traps.

- Ensuring engines are switched off when not required.

- Regular maintenance, tune-ups and exhaust leak checks.

- Reducing the number of workers or the time workers are exposed to areas where

- DEEE are generated. Ensure that other workers not involved with DEEE-generating activities are not exposed to DEEE areas.

- Making sure cold engines are warmed up in spaces with good ventilation.

- Job/task rotation to limit potential exposure times.

- Filtering air in vehicle cabs.

- Providing information, instruction and training on DEEE to workers.

- wearers are face-fit tested and that the RPE fits correctly

- wearers should be clean shaven to ensure a proper skin to RPE seal

- wearers are trained for use of the RPE

- the RPE is cleaned and checked before and after use

- filters and disposable RPE are changed regularly

- RPE is stored correctly

- defects are reported immediately and the RPE is not used if defected or not clean.

Eliminating DEEE

Reducing or substituting DEEE

Engineering controls

Administrative controls

Respiratory protective equipment (RPE)

Appropriate RPE should be provided to all required workers. Ensure that:

RPE is designed to protect wearers from inhaling harmful dusts, fumes, vapours or gases, and should only be used as a last control measure. It is better to control DEEE exposure using other controls. However, for some activities or work tasks, RPE may be the only practicable solution.

Consideration of DEEE assessment in practice

It is important to consider the organisation’s activities and worker’s exposure in the context of real-world situations. We published a study in 2020 on the exposure of 141 drivers in London to DEEEs. This not only demonstrated how DEEE measurement could be done in practice, but also presented some suggestions of control measures that could mitigate the identified exposures. See the download section of this page for the summary and full research report.

Managers and business owners

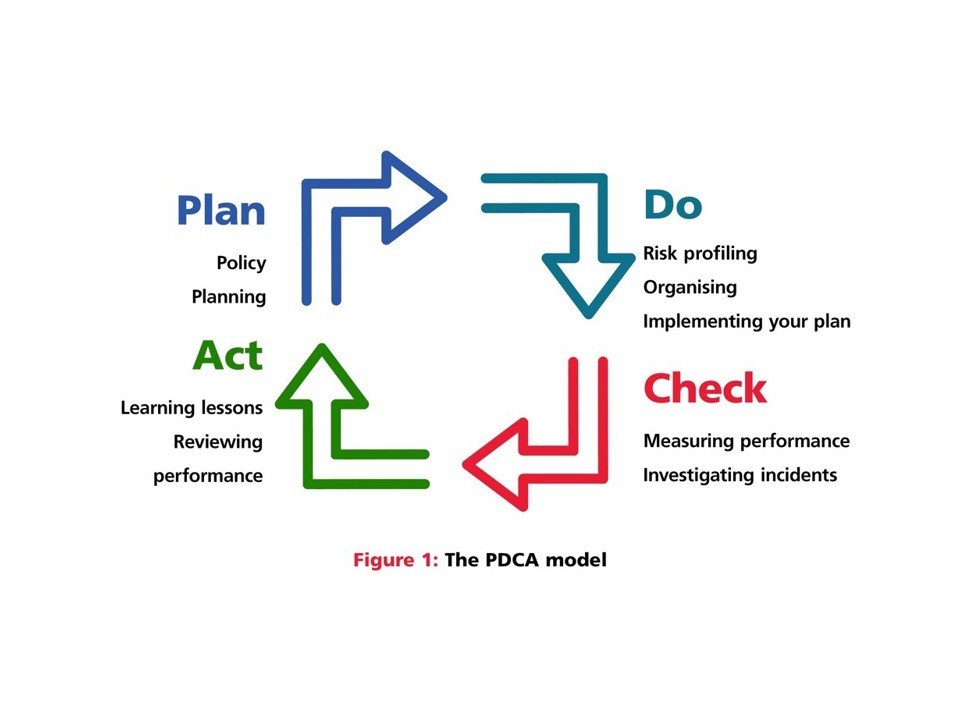

The plan, do, check, act (PDCA) health and safety management system provides eight simple steps to reduce DEEE exposure for workers.

- Are diesel engines or equipment being used in or for the workplace?

- Are DEEE being released into enclosed working areas?

- Are DEEE being drawn into the workplace through ventilation inlets?

- Are DEEE concentrating in confined spaces or areas in buildings where there’s limited air movement?

- Are there clear soot deposits on surfaces in the workspace? Is there a visible ‘haze’ or ‘smoke’ appearance in the air?

- Is there white, blue or black smoke being emitted from diesel engines? If so, how often does this occur?

- Have there been any ill-health complaints from potentially exposed workers – do workers suffer from irritated eyes, throat or lungs, or incur headaches or coughing?

- What tasks will they be doing that may expose them to DEEE?

- How likely is it that workers will be exposed to DEEEs and who could be affected?

- Can exposures be avoided?

- switching to other forms of fuel where possible, for example electric vehicle

- replacing old engines with newer versions with lower emissions

- reducing exposure via engineering controls such as implementing local exhaust ventilation

- implementing administrative controls such as rotating jobs between different workers to minimise exposure and providing training

- providing suitable RPE where required to protect workers.

- if the DEEE exposure plan was accurate and shared

- if local procedures were implemented and followed correctly

- whether those exposed had been informed of the risks associated with DEEE exposure

- whether those exposed had been provided with relevant training and RPE.

Plan

Assign a competent person to manage DEEE risks

Mitigating DEEE exposure is achievable. The responsible person should be competent to undertake the task and start by developing a plan to assess the risks of exposure and consider these points.

Are people competent to manage DEEE? Assessing and managing exposure to harmful substances are specialist areas. If workers do not have the right training, knowledge and experience then a fatal mistake could occur. Seek expert advice if required.

Do

Assess organisational DEEE exposure risks

Consider who might be exposed to DEEE throughout the organisation.

Communicate DEEE risks to workers and contractors

As good practice, whether it is law or not in your country, workers should be informed of the level of risk to health and what precautions they must implement to keep themselves and others safe. Contractors should also be informed of risks.

Apply control measures to reduce DEEE exposure

These will include:

Provide DEEE information, instruction and training

It is good practice to provide DEEE exposure awareness training to workers whose activities may involve tasks with exposure risks.

Check

Investigate DEEE exposure incidents

The investigation must check:

A note should be made in the personal records of those exposed with DEEE-related ill-health. Records should include when the incident happened, how long it lasted, and the outcome of the exposure.

Consider submitting exposed workers to an organisation health monitoring and surveillance programme.

Monitor controls and carry out health surveillance

Monitoring controls is important to check whether they are suitable and working to eliminate or reduce DEEE exposure. Health monitoring can also be important. Workers should undergo regular health checks by a competent medical professional. This may be through occupational health.

Act

Review and integrate lessons learned

After any incident and investigation, lessons learnt must be recognised and applied to the DEEE exposure plan and health and safety management system. This will help to prevent and reduce the chance of exposures recurring.

The DEEE exposure plan should be reviewed regularly. This will ensure it remains as accurate as possible. Good practice would be to complete reviews on an annual basis or sooner, if required. For example, a more frequent review may be required if a large amount of work involves DEEE, as more workers may be at risk.

Occupational safety and health professionals (OSH)

OSH professionals may need to help implement a DEEE exposure plan, liaise with an external provider who is implementing a plan or support with the maintenance of a DEEE exposure system that is already in place.

They will need to work with both managers and workers to help risk assess, implement controls, and eliminate or reduce DEEE exposures.

Tasks may include:

- regularly consult with workers

- provide support with the organisational DEEE risk assessment

- support with identifying and implementing suitable controls by following the hierarchy of controls

- support with the implementation or maintenance of the DEEE exposure plan

- routinely inspect known working tasks and activity areas that may be exposed to DEEE

- check that workers are following and understand procedures and safe systems of work

- source and provide suitable DEEE information and training

- investigate incidents and exposures

- support with health monitoring and surveillance requirements

- support with evaluations and instate any learning lessons to prevent future DEEE exposure incidents.

Workers

Workers should ensure they have been informed about the risks of DEEE exposure and how to avoid them. Here are some examples of what workers can do to protect themselves.

- Follow safe systems of work that are in place.

- Know how to use associated equipment correctly or control equipment and components.

- Be able to detect faults with equipment and know how to report them.

- Be able to use ventilation methods.

- Turn off engines when they are not in use and do not leave them idle, if possible.

- Do not eat or drink in areas known for DEEE exposures and wash hands and face before eating, drinking and leaving the workplace.

- Avoid skin contact with diesel fuel or oil.

- Know how to use RPE correctly.

- Report any symptoms associated with DEEE exposure and visit a medical professional.

- A cough that doesn’t go away after two or three weeks.

- A long-standing cough that gets worse.

- Persistent chest infections.

- Coughing up blood.

- An ache or pain when breathing or coughing.

- Persistent breathlessness.

- Persistent tiredness or lack of energy.

- Loss of appetite or unexplained weight loss.

- driving with the windows closed, so you are not breathing in DEEE

- ventilating vehicles using the recirculate air setting – but this should be used sparingly, as it also circulates carbon dioxide that is breathed out

- planning routes carefully to avoid congested traffic areas and tunnels, if possible

- rotating shifts so they are not always driving at the busiest times on the roads

- considering in-cabin filters, as they can reduce DEEE exposure.

- Petrol vehicles use more fuel than diesel and produce more carbon dioxide but less-toxic emissions.

- In the European Union, Euro 5 and 6 diesel vehicles are required to have a diesel particulate filter, which reduces particulate emissions by up to 90 per cent. Other countries have similar standards.

- Hybrid electric vehicles (HEVs), plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEVs) and all-electric vehicles (EVs) typically produce lower exhaust emissions than conventional vehicles or no exhaust emissions at all.

- Regular maintenance of your vehicle is important in keeping dangerous emissions low.

- Turn off engines if not needed. This stops the production of DEEE.

- Use local exhaust ventilation. Tailpipe exhaust extraction systems are used to draw fumes away from the work area and filter them. Check before use to make sure they have been inspected properly and maintained.

- Use workplace air extraction. Increasing air circulation in the workplace can help reduce exposure to DEEE. This can be done by using installed air vents in the walls and ceiling, or even by keeping doors and windows open in your workplace.

- Wear a mask. For some jobs, you’ll need to wear a mask. Make sure it’s an FFP3-standard mask (European standard EN149:2001 or country equivalent) or a powered air-fed hood.

- Get trained. Understand the dangers of exposure to DEEE, and when and how to eliminate them. Use controls and protective equipment.

Health symptoms

See your doctor if you have any of these symptoms.

Professional drivers

Professional drivers are usually exposed to high levels of DEEE while working. This risk increases when they are working in congested traffic areas and driving at busy times of day.

Protect and minimise exposure to DEEE by:

Your vehicle

Think about the vehicle you are driving. Did you know?

What workers in vehicle workshops and other static workplaces can do

More about diesel engine exhaust emissions

Why fumes still pose a risk

Standards for diesel emissions have been improving steadily over the past 20 years. Many people are now of the view that modern diesel engines are ‘safe’, at least in Europe and North America.

We need to remember there are a lot more diesel vehicles on the roads in our towns and cities and this has offset some of the benefits from cleaner technologies.

Also, there is a mixed fleet – both on the road and off – with many older vehicles and plants still in service. It will take time for exposures to decrease to levels that don’t pose a risk to worker health.

Why MOTs cannot pick up on potentially dangerous DEEE

All diesel engines emit particles into the air. These are very fine particles that in moderate concentrations are invisible to the eye. The MOT test provides a way of checking that these emissions are not excessive, but it does not mean there are no emissions. The test checks two things:

- there is a diesel particulate filter present in the vehicle, assuming it was fitted when the vehicle was new

- there is not excessive smoke – essentially, visible blue smoke.

It is really a fairly crude screening assessment to weed out the worst polluters.

Of course, MOTs in the UK only apply to on-road vehicles. Emissions from new off-road vehicles and other diesel engines used in construction, mining, quarrying, railways, agriculture, etc have been regulated in the EU since 1997. However, these standards are less demanding than for on-road vehicles and there is no real ongoing assessment of the acceptability of engine emissions such as with the MOT test.

Why DEEE are still an issue outside

Natural ventilation outside may provide adequate control, but you need to consider:

- how likely it is that workers will be exposed to DEEE

- how many of them

- to what extent

- for how long

- whether the exposures can be avoided.

If exposure to diesel fumes is likely, then other actions may be needed. Check out our guidance in the section on how to manage exposure.

UK enforcement activity

DEEE are covered by the Control of Substances Hazardous to Health Regulations 2002. Health and Safety Executive inspectors look for prevention or control of exposure to hazardous substances in the workplace. They will take enforcement action where risks of exposure are not effectively managed.

IOSH

IOSH